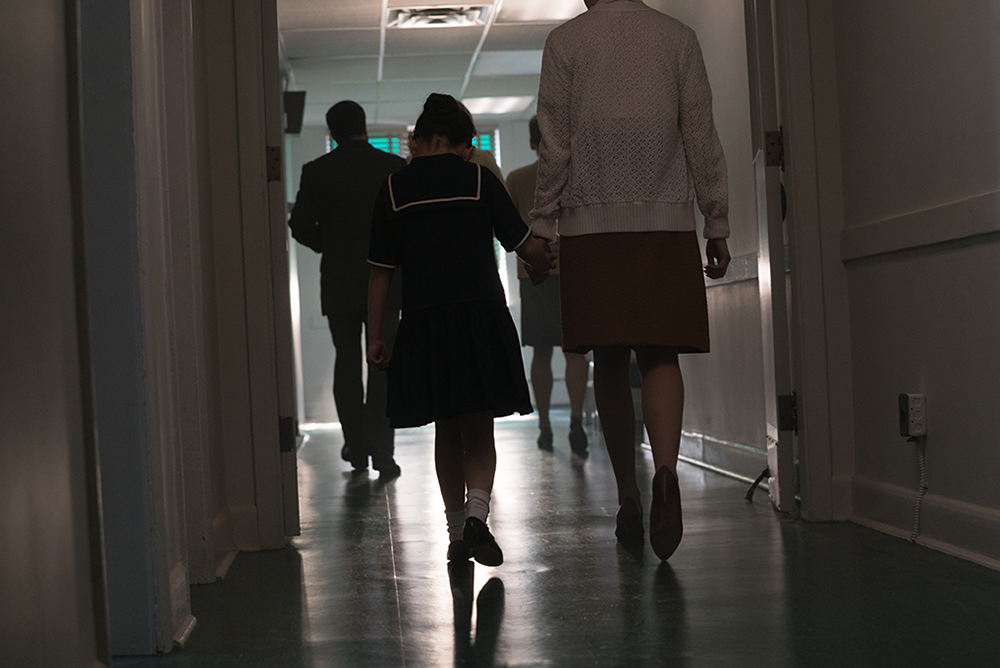

On-set of Little Bird drama series | Credit: Coming Home (Wanna Icipus Kupi)/Larry Carey/Rezolution Pictures Inc.

Editor’s Note: This article contains potentially triggering material including discussions of child abuse, kidnapping, racism and racial violence.

In the U.S. and all over the world, residential schools, or Indian boarding schools, forcibly fractured Indigenous cultures. The implication that these institutions were just “schools” does little to paint a picture of the human rights violations and historical trauma suffered by whole communities. The reality is that governments and churches used residential schools to systematically separate, abuse and indoctrinate Indigenous children. Even today, society at large — and, more importantly, the impacted Indigenous communities — struggles to comprehend an arrangement designed to scrub away culture. The history of the residential school system is perhaps best known in Canada, particularly as the media covers ongoing discoveries of mass graves and other indications of deep-seated systemic corruption. However, similar institutions existed in the U.S. and across the world — and now, Survivors everywhere are coming together to tell their stories. The PBS drama “Little Bird” shares one such story inspired by real events, reflecting the heartbreaking and tragic challenges that residential school Survivors did or could have faced. The making-of documentary — “Little Bird: Wanna Icipus Kupi (Coming Home)” — tells one that belongs to only a few. It captures the experiences of the Indigenous people who brought “Little Bird” to life by drawing on their own experiences. Read on to learn more about residential schools and their ongoing impact as explored in “Little Bird: Wanna Icipus Kupi (Coming Home).”

Although it may be difficult to comprehend the “why” behind residential schools, it’s important to understand the “what.” These institutions, sometimes called “federal Indian boarding schools” in the U.S., weren’t really about learning math and spelling. Funded by governments and generally run by various Christian denominations, residential schools housed abducted Indigenous children far away from their families and often punished them for any display of their native language, customs, beliefs or values (1, 2, 3). They were a thinly veiled — and, in many cases, completely candid — attempt to eradicate cultures viewed as inferior, unsophisticated and even “savage.”

U.S. military officer Captain Richard Henry Pratt, whose now-famous speech in 1892 was foundational to the ongoing development of residential schools in the U.S. and abroad, put it this way (4): “A great general has said that the only good Indian is a dead one, and that high sanction of his destruction has been an enormous factor in promoting Indian massacres. In a sense, I agree with the sentiment, but only in this: that all the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.” (4) The PBS documentary “The American Buffalo” takes a closer look at this and other impacts on Indigenous culture over 10,000 years of North American history, including Pratt’s philosophy. This view reflected a society that viewed itself as impeccably civilized and was bent on forcing its views and values upon Indigenous peoples. It even claimed to be “saving” these children (3). Of course, not everyone was silent. Indigenous parents fought desperately to hide and otherwise protect their children. Families searched whole cities and fought for custody in a system designed to overpower them. In Canada, Indian Affairs chief medical officer Peter Bryce visited schools in the western part of the country and reported that around 25% of children died — sometimes up to 75% in a single school (5). He warned that these conditions were inhumane. Officials chose to ignore these warnings.

Brokenhead Ojibway Nation | Credit: Coming Home (Wanna Icipus Kupi)/Larry Carey/Rezolution Pictures Inc.

Altogether, residential schools began in the early 1800s and ran for more than 150 years (3, 6, 7). The last school in Canada closed in 1996. During that time, an estimated 150,000 children attended these schools and at least 6,000 died there — in Canada alone (3). Even today, researchers are still finding unmarked graves on residential school sites (8). Tragically, this story isn’t exclusive to North America. Similar schools could be found in Ireland, New Zealand, Sweden and South Africa (9, 10). Often called the “industrial school” system, these institutions helped dismantle any local or Indigenous community that posed a perceived threat to “progress” while preparing new generations to become undereducated, assimilated workers for lower-paying jobs (2, 9, 10).

In many ways, Indian residential school was a life sentence. The brutal treatment in residential schooling began long before a child walked through the doors. “Little Bird” tells the story just as many real Survivors experienced it: The show’s protagonist, five-year-old Bezhig Little Bird, was kidnapped while playing outside and taken from her family on false accusations of abuse and neglect. We see her mother fight and beg to protect her, and her father violently beaten for trying to stop the kidnapping — but to no avail. The same events played out across the history of residential schools. Children were forcibly separated from their parents and taken far from the community, surroundings and Indigenous culture they’d always known. For example, in his memoir “Recollections of an Assiniboine Chief,” Survivor Daniel Kennedy (Ochankuga’he) recalls being “lassoed and roped” at the age of 12 and taken against his will (3).

Once a child arrived at the “Indian boarding school,” assimilation began immediately. Kids had their hair cut short, clothes replaced with uniforms and names changed — sometimes including further dehumanizing identification numbers (2, 3). Because schools were often segregated by gender, many kids were also separated from their siblings (3). They were placed in uncomfortable, unsanitary conditions without proper medical care or sufficient nutrition. Worse yet, the children were subjected to emotional, physical and sexual abuse for years on end. Some tried to run, but were almost always caught again (2, 3, 5). We see this in “Little Bird” when Bezhig sneaks through the halls of the school to find the younger siblings forcibly separated from her. She leads them on a desperate escape attempt and is discovered before she can get back to their family, who we see searching the streets for them.

Schedules in these Indian residential schools were strictly regimented. A significant portion of the day was dedicated to work. Unpaid labor was touted as “building practical skills” but was actually an effort to keep the underfunded schools running. When children were allowed to go to proper classes, they didn’t follow the same curriculum as their non-Indigenous peers; instead, they were primed for domestic service and maintenance work without any support for higher education or career advancement. They generally received nothing higher than elementary-level education — not only barring them from future opportunities but perpetuating the belief and expectation that Indigenous communities were intellectually inferior (2, 3).

Rather than addressing these issues, the Canadian Department of Indian Affairs and other agencies made empty promises or looked the other way. Some even used the poor conditions as opportunities for experimentation (2). For example, between 1948 and 1952, nearly 1,000 Canadian children in residential schools were used as subjects in tests on nutritional supplements — or lack thereof (5). In the U.S., Federal Indian boarding schools spread across the country. One well-known example is the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, which operated for nearly 40 years, housed children from more than 140 tribes and acted as the inspiration for several other institutions (11). These inhumane conditions inevitably led to health concerns, particularly tuberculosis (TB) — a highly infectious disease marked by coughing, weakness and fever (5, 12). Bryce’s report on Canadian institutions identified TB as a common cause of death and one that was far from inevitable; he pointed out that the schools’ poor construction, nonexistent medical care and tendency to house sick students with healthy peers were all responsible for the spread and severity of TB infections. Even when children grew up and left the system, poor care and nutrition during their younger years led to chronic conditions over time (5). Worse yet, these schools often sent critically sick kids to segregated hospitals that were severely underprepared and underfunded. Parents and families were rarely informed about a child’s health condition, location or, in worst-case scenarios, burial site. To this day, some families still don’t know what happened to their relatives who never came home from residential or industrial schools (5).

As residential schools continued to have negative impacts on Indigenous communities — and, by extension, entire economies and societies — governments finally took notice. The concept of Indigenous boarding schools was progressively abandoned in favor of the child welfare system (2). Unfortunately, this led to further disruptions and tragedies: Indigenous children were taken from their homes and placed with adoptive families of an entirely different culture, belief system and societal status (2). This period is called the “Sixties Scoop” — a history covered at length in “Little Bird,” where we see Bezhig adopted by a non-Indigenous family and assimilated into their culture and beliefs. We also see how this affects her sense of identity and belonging — and how far she goes to find the family she was taken from. Simply put, although the chapter on residential schools has closed, the impact of this system and the experiences it created cannot be erased.

Sioux Valley Dakota Nation | Credit: Coming Home (Wanna Icipus Kupi)/Larry Carey/Rezolution Pictures Inc.

More recently, the U.S. and Canadian governments and some church officials have taken steps toward some level of reconciliation — a formal attempt at making up for something that can’t be forgotten and may never be forgiven. For example, Pope Francis issued an apology for residential school systems in 2022. The Pope also took a trip to Canada and pledged that the Catholic Church, along with the Canadian government, would pay millions of dollars in reparations. However, Survivors point out that these are just the first steps in a far more complicated journey toward reconciliation. Most also say that apologies won’t mean much until certain groups take full responsibility and recognize the impact of past actions. Similar attempts at reconciliation include:

The Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement, which established a Canadian commitment to public apology and financial support but neglected at least one group of Survivors (7, 13). The National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, a home for all the resources and information gathered by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC). The Carlisle Indian School Project, a digital database covering records specifically related to one Pennsylvania school. The documentary “Home From School: The Children of Carlisle” tells the story of a project to bring the remains of children who died at Carlisle back to their families.

Survivors, governments, church officials, researchers and even those not directly impacted by residential schooling all have a part to play in this process. One of the most important lessons is knowing where and how to listen.

Different people have different ways of handling current and historical trauma. Unfortunately, some kinds of closure remain permanently out of reach — particularly because records of Indigenous people and their names, cultures and backgrounds have been systematically forgotten or destroyed. For example, we may never know the names of the children in the recently uncovered graves on residential school sites — which means their loved ones won’t find answers (8). Similarly, children who survived residential schools may be cut off from their blood relations because they don’t have the names and paperwork that would lead them home.

Fortunately, where there are stories to be told, there are people to listen. Survivors are coming together to share their experiences, find connections and perhaps even heal by building new communities. That’s exactly what you’ll see in “Little Bird” and “Little Bird: Wanna Icipus Kupi (Coming Home),” plus an even more personal example of Indigenous storytelling.

“Little Bird” is a limited dramatic series led by an Indigenous creative team. It tells the interwoven stories of residential schools, forced adoption and reconnecting with lost family — all created with input from the perspectives of people who were close to the real events.

This documentary goes behind the camera to show viewers how “Little Bird” came to life. It’s an emotional, deeply personal look at making art that matters, particularly because the creative team and crew can all relate to the story in one way or another.

Mike Mabin, an enrolled member and citizen of the Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians of Montana and the President and CEO of Agency MABU, shares a story from the Crow Creek Indian Reservation in Stephan, South Dakota: “On a more uplifting note, the spirit of Indigenous people wasn’t exterminated. Survivors, along with their children and grandchildren, are reviving their nearly lost culture, history, traditions, language and Native ways. “For example, my youngest son recently visited the Indian reservation in South Dakota where my mom (his grandma) was sent to boarding school. Today, there is a modern-day school located on the grounds. It is run by the Crow Creek Tribe and is providing culturally focused, contemporary teaching to Native American children today. Despite the government’s attempts to eradicate the Indigenous people and cultures in Canada and the U.S., positive change is occurring.”

To some, residential schools may seem like an impossible horror. To others, these stories are very real — and they continue to impact communities, families and individuals throughout the world. No matter how close you are to these experiences, it’s always necessary to listen to those who need to be heard. There are many ways to do that. From researching the history of residential schools in your area to engaging with art made by Indigenous peoples, you can take part in this worldwide conversation. Learn more by watching “Little Bird” and “Little Bird: Wanna Icipus Kupi (Coming Home)” on PBS.